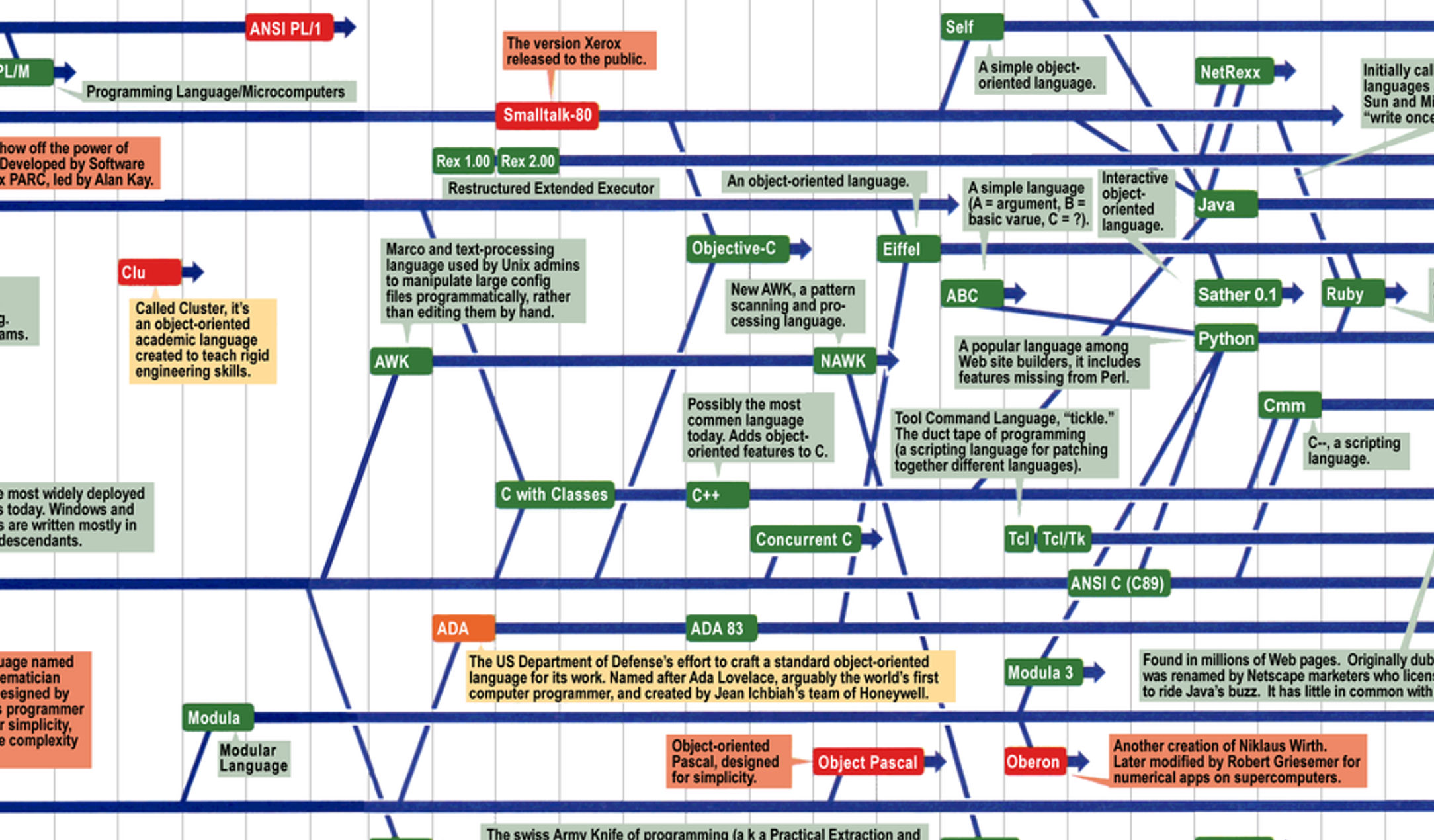

My entry to Quantum Chemistry programming

In 1995, after two years of studies, I got a summer-job at University of Helsinki Laboratory of Physical Chemistry to develop Molecular Quantum Mechanical software with Tuomas Lukka. It was an experience of diving to the deep end with limited preparations and become a lesson about the mixed nature of success in scientific research.

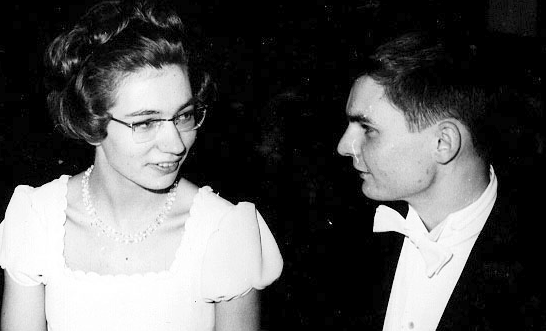

My father Jaakko Brotherus and mother Ulla Brotherus met each other in 1960's at Helsinki University where they were both studying Chemistry. Jaakkos close study mates Pertti Törmälä and Jouko Korppi-Tommola later become professors of Polymer Chemistry and Physical Chemistry respectively. Jaakkos own academic career in Biochemistry was also proceeding well and he would have probably got far, but unfortunately he died in 1981 at age of only 36 when I was 7 years old.

My parents Ulla and Jaakko at Helsinki University Chemists (HYK) party in 1968

When my father was alive, he worked long days in his biochemistry research, so I did not get to know him very well, but he was still able to instill a sense of interest towards science for me. So despite his early death (or perhaps even to some degree because of that) I also wanted to pursue an academic career in Biochemistry. After focusing on natural sciences at the Atlantic College high school in UK, I was considering applying some USA Universities. But through some discussions I come to the belief that it would be equally good to do the basic science degree in Finland and then proceed with PhD in UK/USA.

So I returned to Finland and started studies at University of Helsinki in autumn 1992. But in order to apply to study Biochemistry one first needs to study general chemistry for one year, so I started with the basic courses in Chemistry along with courses in subsidiary subjects of Mathematics and Physics.

Since my IB-studies at Atlantic College went further in Chemistry, Physics and Mathematics than the corresponding courses in Finnish high-school system, I was able to progress initially relatively quickly, finishing in my first year about 30% of the courses towards Masters degree. Those courses included in the 1993 spring-term one of the Physical Chemistry courses. I got fascinated by the promise of Physical Chemistry of understanding molecules and reactions on a deeper level.

After the first year, in fall of 1993, I took a one-year break from my studies to do the compulsory Finnish army service. When I returned in fall 1994 for my second year of studies, I decided to delay the application for biochemistry by another year to do more of the chemistry courses, especially in Physical Chemistry.

On the Physical Chemistry lab-courses in spring 1995 my teaching assistant was Tuomas Lukka, a Finnish science prodigy, who was at the time only 19 and in summer 1995 would become the youngest person in Finland to obtain PhD at age of 20. Tuomas saw my budding enthusiasm for Physical Chemistry and encouraged me to progress on that path. Tuomas (whose work in the Physical Chemistry Laboratory started with summer-work in 1993) suggested he could talk to the Physical Chemistry professor Lauri Halonen to hire me in summer 1995. The plan was to do some vibrational quantum chemistry software project with Tuomas. That seemed like great opportunity for me and Tuomas recommendation seemed to be convincing enough for Halonen, so I was hired.

Tuomas Lukka in 1995

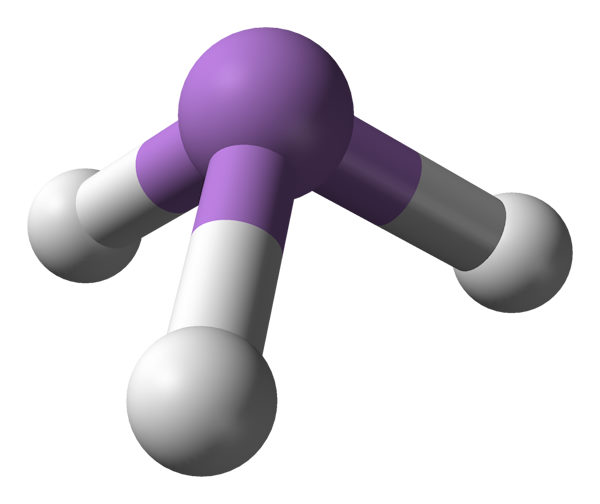

New flexible form for vibrational wavefunction

The research-group of Professor Halonen focused on understanding different vibration-rotation states of small molecules, area which is part of Quantum Chemistry, also called Molecular Quantum Mechanics. In accordance with quantum mechanics, movement on atomic level progresses as a wave. In a looping motion such as vibration of molecular bonds or rotation of the molecule, only some wavelengths of these waves are stable. Just like when you pluck a string of a guitar, only the natural frequency of the string and it's overtones remain while other frequencies die out. These natural frequencies and their overtones form the characteristic quantum-mechanical bound state energy levels of the molecule.

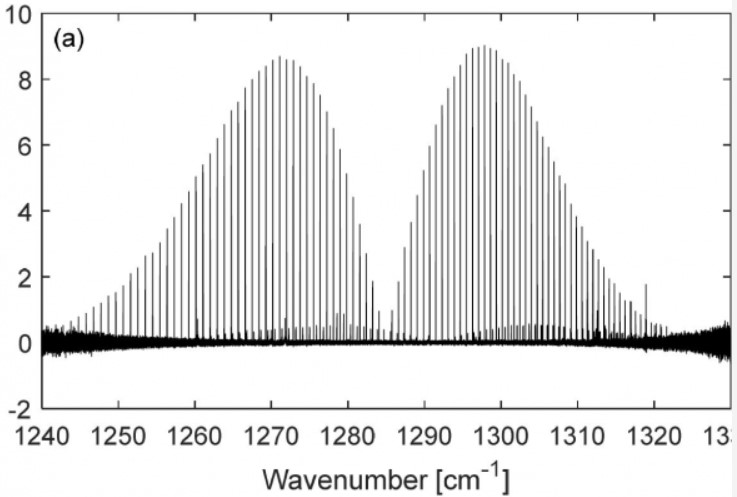

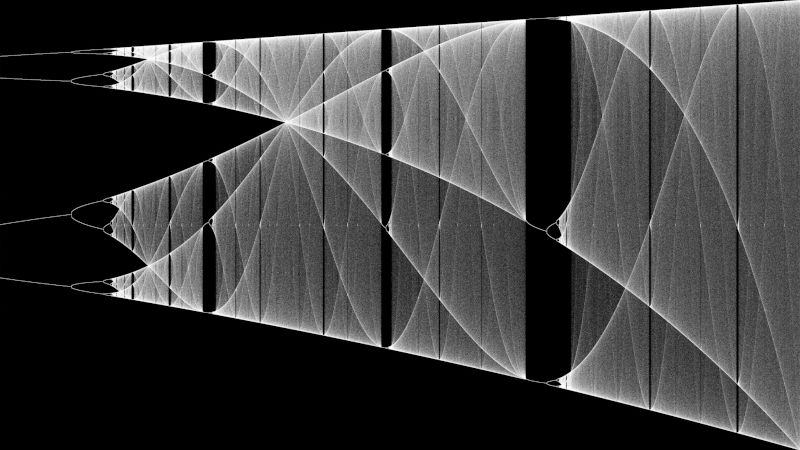

When molecule encounters a photon of light whose energy exactly matches the difference of its current energy level and some higher energy level, it can absorb the light and transition to the higher energy state, producing a spectrum line at the frequency of that photon. Since the energy levels corresponding to molecular vibrations are typically on the scale of infrared light photons, the transitions between vibration-rotation states produce set of spectral lines in the infrared area. Such spectral lines are measured with infrared spectroscopy, which hence was the main experimental method in the research group.

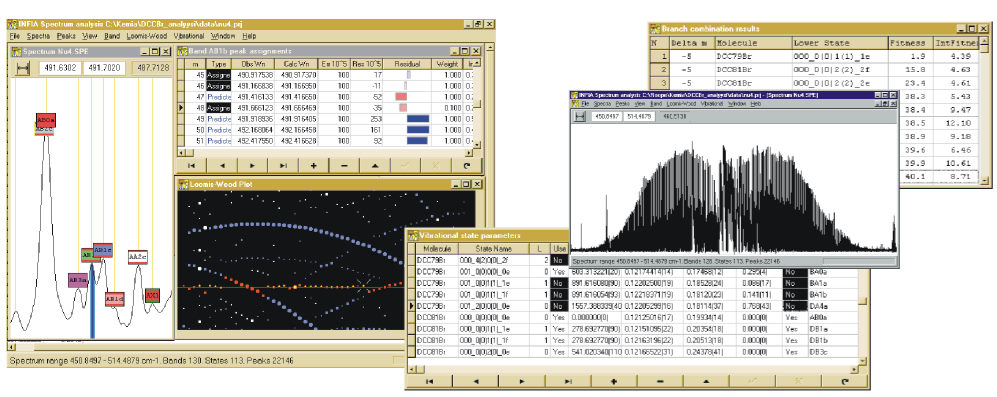

Example of vibration-rotation infrared spectrum band of linear molecule (NNO)

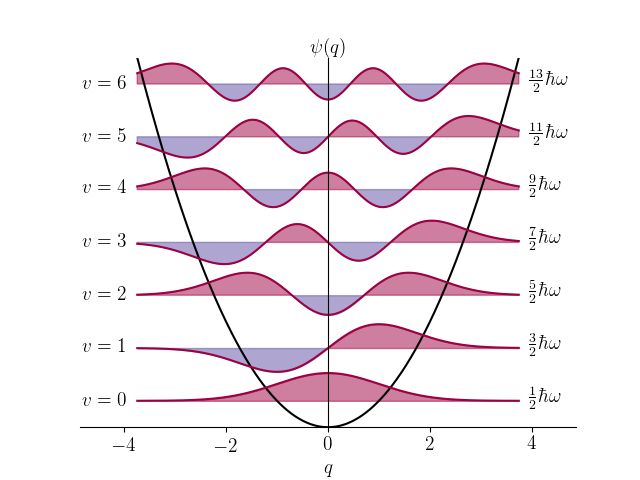

The quantum mechanical analysis of a molecule therefore involves determining the wavefunctions end energy-levels of its various vibration-rotation states. The wavefunctions and corresponding energy-levels are calculated using the time-independent Shrödinger equation which includes Hamilton Operator describing molecules relevant properties like weights of its atoms and length and strength of the bonds between the atoms. Hence the solution of the equation will reveal the structure and internal forces of the molecule.

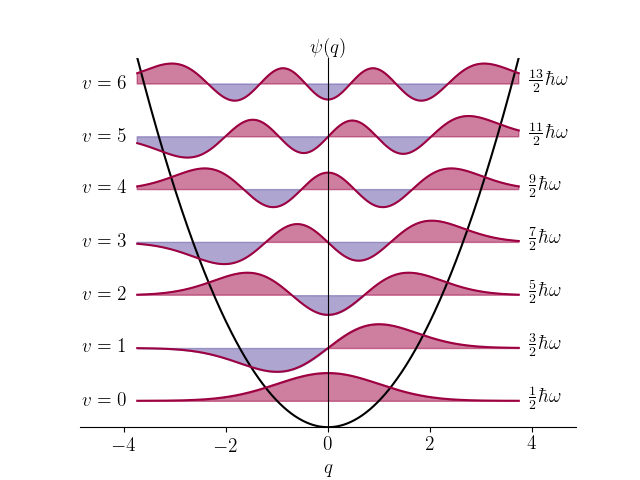

Some wavefunctions for harmonic oscillator, the simplest model for molecular vibrations

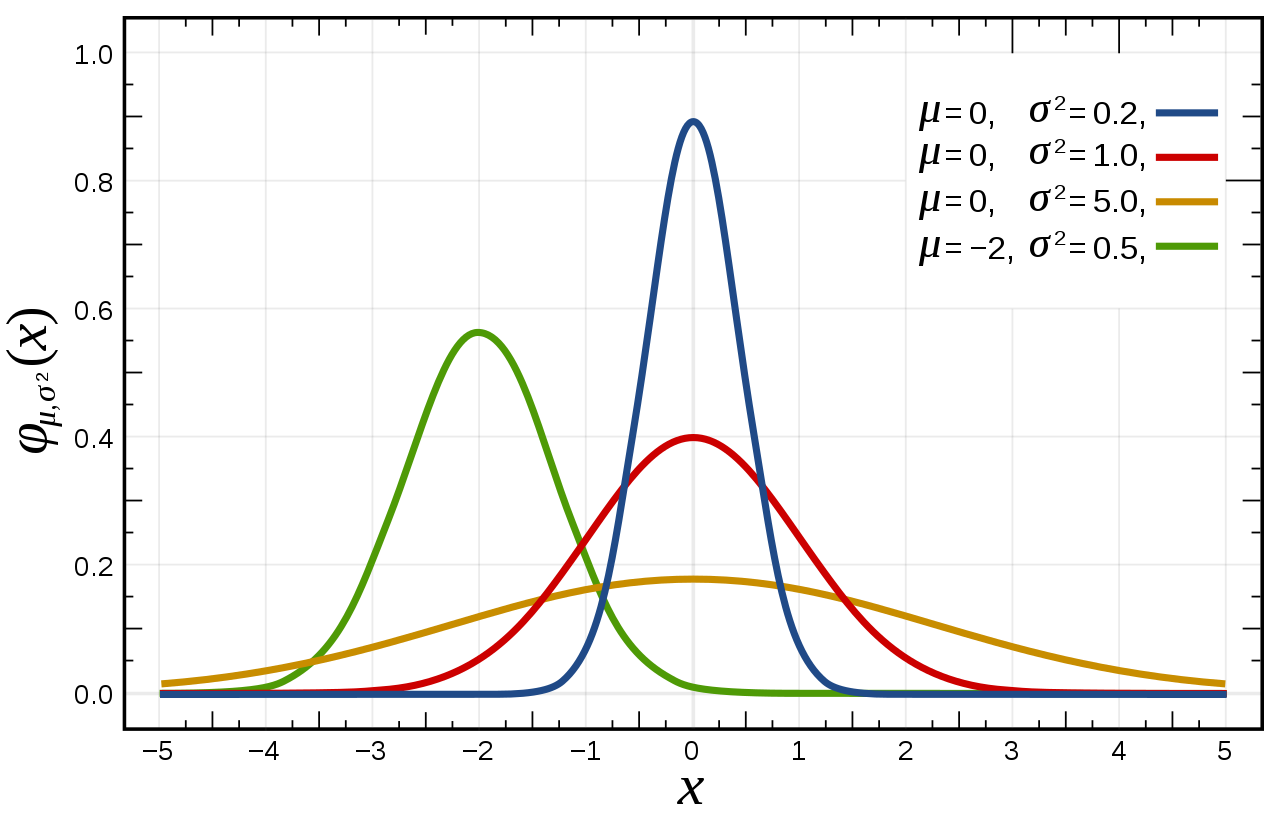

The exact solution of the vibrational Shrödinger equation is mathematically impossible for real molecules and therefore various approximations are used. One of the main ways is to approximate the wavefunction as a linear combination of orthogonal basis functions, typically Hermite polynomials multiplied by Gaussian functions, which are also solutions for harmonic oscillator. Any vibrational wavefunction can be approximated to arbitrary precision in this way and this method reduces the solution of the Shrödinger equation into calculating matrix inversion where the size of the matrix corresponds to the number of basis functions.

Some Gaussian functions, more well-known from statistics of Normal Distribution

The problem in this approach is that for some molecular wavefunctions the polynomial expansion converges slowly ie one needs to take very many terms from the polynomial expansion to accurately model the wavefunction so that the resulting matrices become prohibitively large and slow to invert even on a supercomputer.

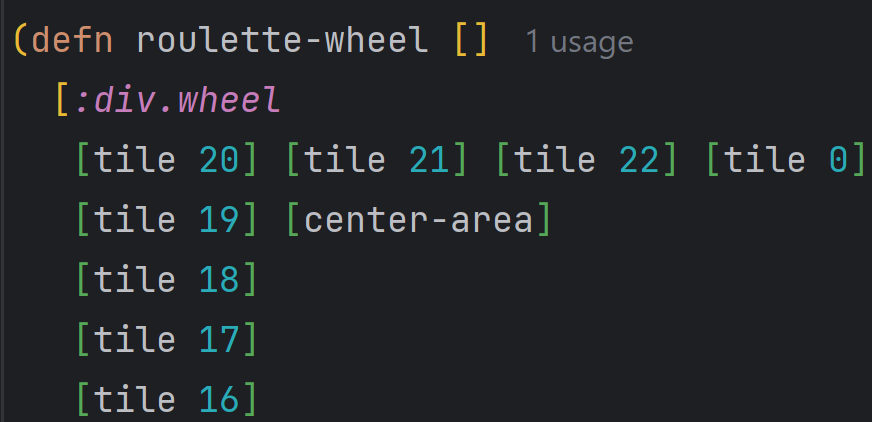

Which brings me to the idea that Tuomas was proposing for our summer-project: instead of modeling the wavefunction as a linear combination the harmonic oscillator wave functions (each with single Gaussian envelope), we would use a more complex basis functions each involving multiple Gaussian envelopes. While such basis functions are more complex and slow to compute with, Tuomas expected that for some molecular cases they would converge so quickly on the real wavefunction that the overall calculation effort would be smaller.

Programming starts

After some initial discussions with Tuomas and Halonen, I started daily work in May 1995 in the Physical Chemistry laboratory, which had just been moving to the newly built Kumpula Chemistry campus. I sat in the spectroscopy lab next to the big laser-spectrometers programming with my Toshiba Portege laptop.

Helsinki University new Kumpula Chemistry campus main entrance

Having recently learned C++, I proceeded in implementing the required calculations software in Borland Turbo C++. Unfortunately none of the source code survives to this day, but in one email I sent to Tuomas about profiling the software we can get impression to some of the C++ classes I used to represent the wavefunction and some of the functions performing the calculations:

Turbo Profiler Version 2.1 Fri Jun 09 16:21:15 1995

=====================================================

PGIntProduct 1.7657 sec 7%

Coeffmap:: [] 1.6308 sec 6%

Coeff::oper < 1.3935 sec 6%

InfiniteIntegral 1.3771 sec 6%

PG::Product 1.3046 sec 5%

Coefnode::create 1.1392 sec 4%

Coefmap::next 0.9290 sec 3%

Coeff::oper == 0.7046 sec 2%

BinomyCoeff 0.5678 sec 2%

C++ was probably not the ideal tool for this kind of semi-symbolic semi-numeric mathematics. I was not yet aware of Mathematica, which would have been much better. But C++ was nevertheless more flexible than Fortran 77 which was the language of choice of Lauri Halonen and his generation of Quantum Chemists.

Me and my Toshiba Portege laptop in 1995

It was not easy project for me to get started with. During my two years at the University, I had completed the basic Physical Chemistry courses, but none of the advanced ones which deal more with vibrational spectroscopy and related quantum mechanics. So I had to absorb quite a bit of new theory during the work. Support from professor Halonen was quite minimal, but I guess that was expected since the idea was from Tuomas and he had marketed the project to be between him and myself. Unfortunately even Tuomas himself had limited time to participate in the work due the frenzied push to complete his own PhD that summer.

This meant that the actual software development fell 100% on me. And during June and July we met a few times with Tuomas and exchanged a total of 22 emails discussing various developments and challenges in the science, mathematics, programming, optimization, bugs and performance of the emerging software.

In the first these emails on 2.6.1995 I report that I had completed some significant parts of the code:

Date: Fri, 2 Jun 1995 12:00:37 +0300 (EET DST)

From: Robert Brotherus

To: Tuomas J Lukka

I have completed the calculation of the wavefunction derivatives

with respect to parameters (the last distinct modules) and summary

function that calculates the optimization target W derivatives for

parameters. I have now added quite much code without intermediate

tests, so I will next do more testing. Next I will proceed to making

the loop for optimizing the parameters. I don't expect that to be too

difficult, but I am wondering about how to choose suitable

step size for the optimization.

The subsequent emails show occasional confusion about correct form of the various derived formulas, such as following email-exchange happening over several days later in June:

From: Robert Brotherus (1995-06-05)

[...] So I will proceed to normalize the wavefunction in the beginning

and after each iteration step.

From: Tuomas J Lukka (1995-06-05)

[...] Will not work! The derivatives will become invalid.

Must use: W = f1 * f2 = 1/(^2) * ( - ^2)

From: Robert Brotherus (1995-06-06)

[...] Indeed so. And for each parameter dW/dA one must then recalculate:

dW/dA = df1/dA * f2 + df2/dA * f1

From: Robert Brotherus (1995-06-09)

[...] Currently I am focused on determining whether the program is

calculating the parameter derivatives incorrectly (I suspect this is the

case) and if there is any other reasons for the slow convergence

of the optimization.

From: Tuomas J Lukka (1995-06-12)

[...] Have you tried making the optimization step relative

to the steepness of the gradient?

From: Robert Brotherus (1995-06-13)

[...] I was able on Monday to fix a stubborn bug that had been in the

derivative functions. Now dW/dA produces same result as manually

calculated derivative approximation (W(x)-W(x+d))/d.

However, when normalized to d(W/^2) it still produces

different results from manual calculation. Come and see tomorrow

if you have time.

From: Robert Brotherus (1995-06-14)

I found there was an error in the way to normalization was handled

and I was able to fix this today. You were earlier proposing as

the normalized function:

> W = f1 * f2 = 1/(^2) * ( - ^2)

I implemented this. But it turned out it does not work.

The correct form is:

W = / - (/)^2

I was very happy to see that after this fix the analytically

calculated derivatives started to correspond to manual ones

for all parameters.

From: Tuomas J Lukka (1995-06-14)

> I implemented this. But it did not work.

Oops, I apologize!

> derivatives started to correspond to manual ones

YEEEEEEES!

The results seem now VERY encouraging!

Encouraging, but No Cigar

In the last weeks of June I still write Tuomas about fixing a problem in convergence for higher-order terms and fixing a bug in routine determining optimization step-size. I reported that all our test-cases now converged from initial 10% errors to correct results in less than ten iterations - something that we initially considered sufficient goal for the project.

Yet, the project turned out to be a dead-end. In the beginning of July we had a meeting with Tuomas and professor Halonen where it was agreed that while the new form of the wavefunction could be used to calculate all the vibrational cases we tried out, it did not seem provide the combination of better accuracy and lower computation requirements than the traditional method. I have no detailed memories of this discussion and there is no written record about the decision to abandon the project. But I had no expertise to doubt the conclusion and of course it's better to fail fast when an effort is futile rather than waste even more time on an apparent dead-end. Last written record about the project is an email where I describe final deployment of the software to the University mainframe computer:

Date: Mon, 10 Jul 1995 16:52:17 +0300 (EET DST)

From: Robert Brotherus

To: Tuomas Lukka

Subject: Last changes to the program

The software is now compiled and running on the Kruuna

mainframe computer. For ease of use, I added support for

command-line parameters defining the input data.

Try it out! As one can guess, it runs 10x faster on Kruuna

than on my own laptop.

After that the project, the program and its source-codes were abandoned and lost. It resulted in no publication or report and was not used towards my thesis work.

I do remember I was slightly disillusioned by this outcome. Earlier, when I had been enrolling on any university courses and classes, I had been getting used to the idea of working hard, doing well in exam, passing the course and getting credits that nudged me towards completion of a formal degree. But now I got the first disturbing glimpse of the uncertainty and risk in real research: When trying out something genuinely new one could work hard, resolve challenging problems and get the work done - and still arrive to a dead-end. Of course one would still learn something and get paid salary, but the effort would essentially go to waste because the results failed to improve on the scientific state-of-the-art. No publication, no credits, no progress towards a formal degree, no going ahead in academic career.

Joining the staff

Nevertheless, after the summer, Professor Halonen gave me a permanent job as a research- and teaching assistant in the Physical Chemistry lab. So in the fall of 1995 I started guiding students in the laboratory courses of Thermodynamics, Dynamics and Structure of Molecules. And I started working on other software projects in molecular quantum mechanics and infrared spectroscopy. And I still needed to continue studying various chemistry, physics, mathematics and computer-science courses needed for the masters degree.

While at that point I remained fully dedicated to the idea of a life-long scientific academic career, it seemed clear that it was not going to be in Biochemistry like my father but in Physical Chemistry.

Physical Chemistry Laboratory staff in summer 1996, one year after my starting as a permanent member. From left: Jorma Seetula, Susanna Tuomisto, Jouko Hytömäki, Kari Tuomainen, Tuula Fontel, Matthias Horn, (?), Professor Lauri Halonen, (?), Juha Lummila, Kaarlo Kalliorinne, Robert Brotherus (myself), Esa Isoniemi, Mika Petterson, Martti Paakkunainen, Janne Pesonen, Leonid Khriachtchev, Maria Saarinen, Vesa Hynninen, Olavi Vaittinen, Professor Markku Räsänen, Dimitri