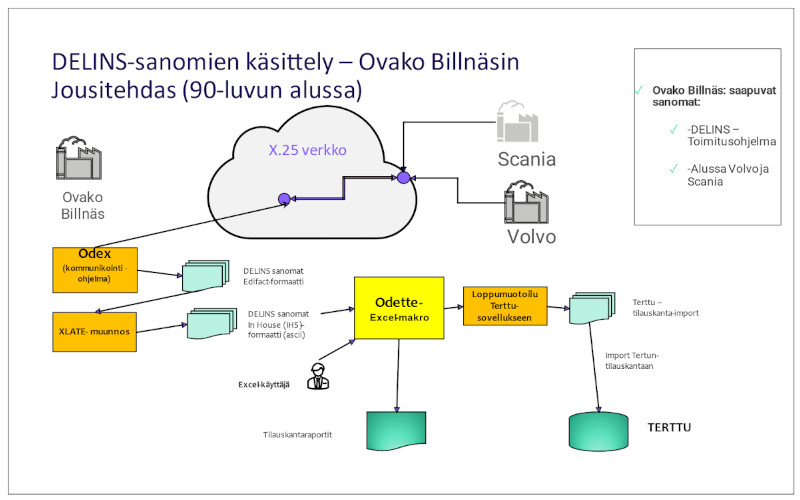

Developer experience in 1987 with C64 vs modern tools

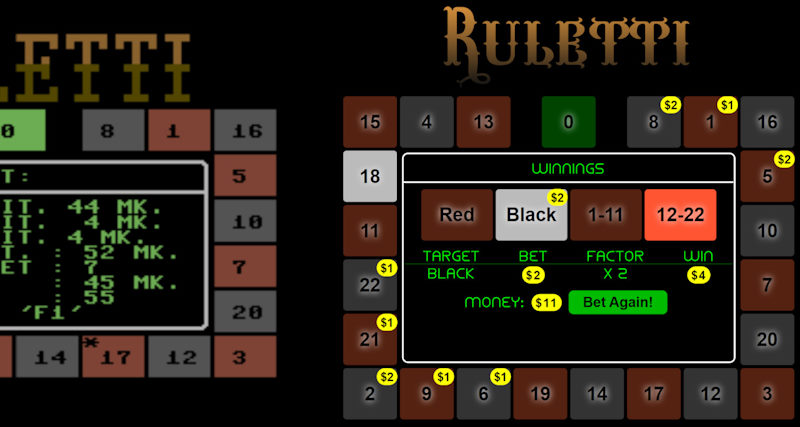

Earlier I was introducing the old Commodore 64 "Ruletti" game I wrote in 1987 and the new Ruletti-reframe webapp-version I made with modern functional-reactive style. In the latter article I was comparing the versions from users point of view regarding usability, visuals and sounds. The other side of the story is from developers point of view: what was it like for an average hobbyist to write a small game like this with Commodore 64 in 1987 compared with a modern PC today?

Stable zero-startup vs. Evolved power

One nice feature of Basic-programming with a physical Commodore 64 is the startup-time: You flick on the power-switch and in two seconds you have a prompt ready to start writing some lines of Basic-code. The whole OS and Basic-interpreter are in ROM and immediately available.

Contrast this to my current ClojureScript-setup: In addition to installation of OS on the PC, one needs installation of IntelliJ IDEA editor and Cursive-plugin for Clojure. Launching the PC from power-on to the editor being up-and-running takes at least a minute. Further, to get coding and compiling the project, one needs to install node.js and Leiningen build-tool and then initiate new project with command lein new re-frame ruletti.

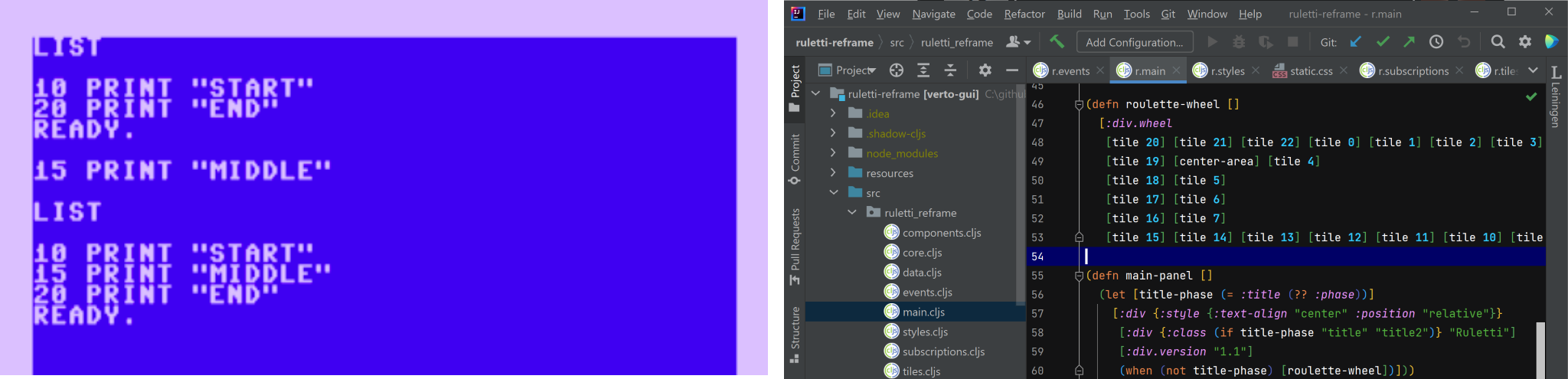

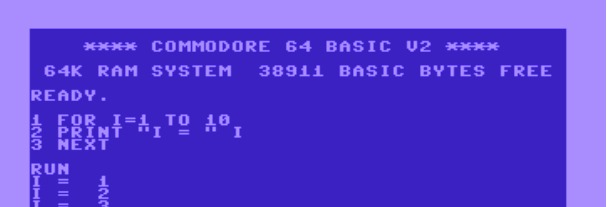

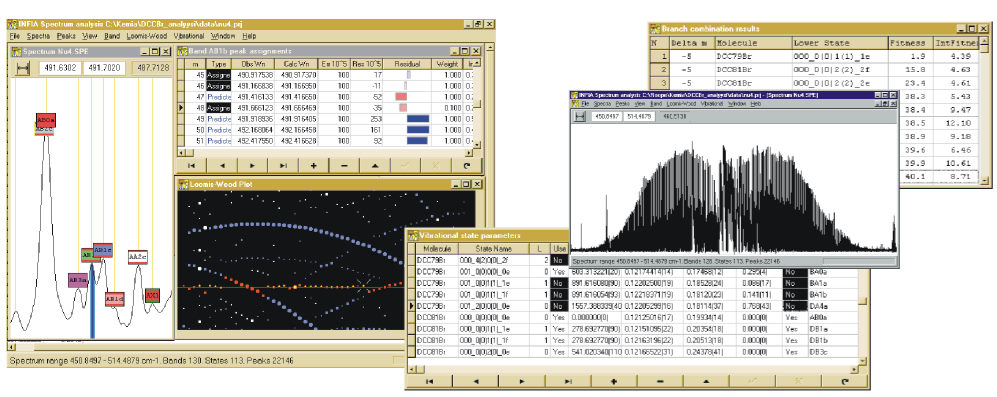

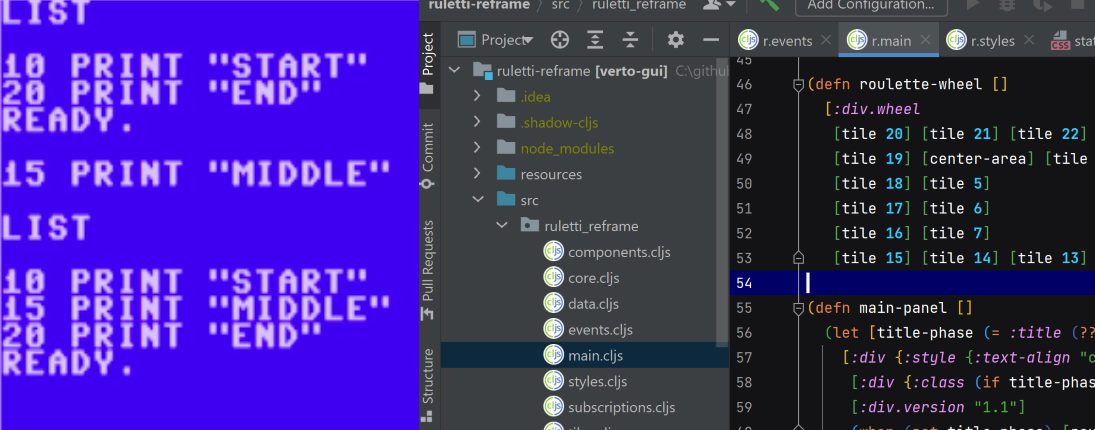

Commodore 64 basic-environment and IntelliJ IDEA IDE:

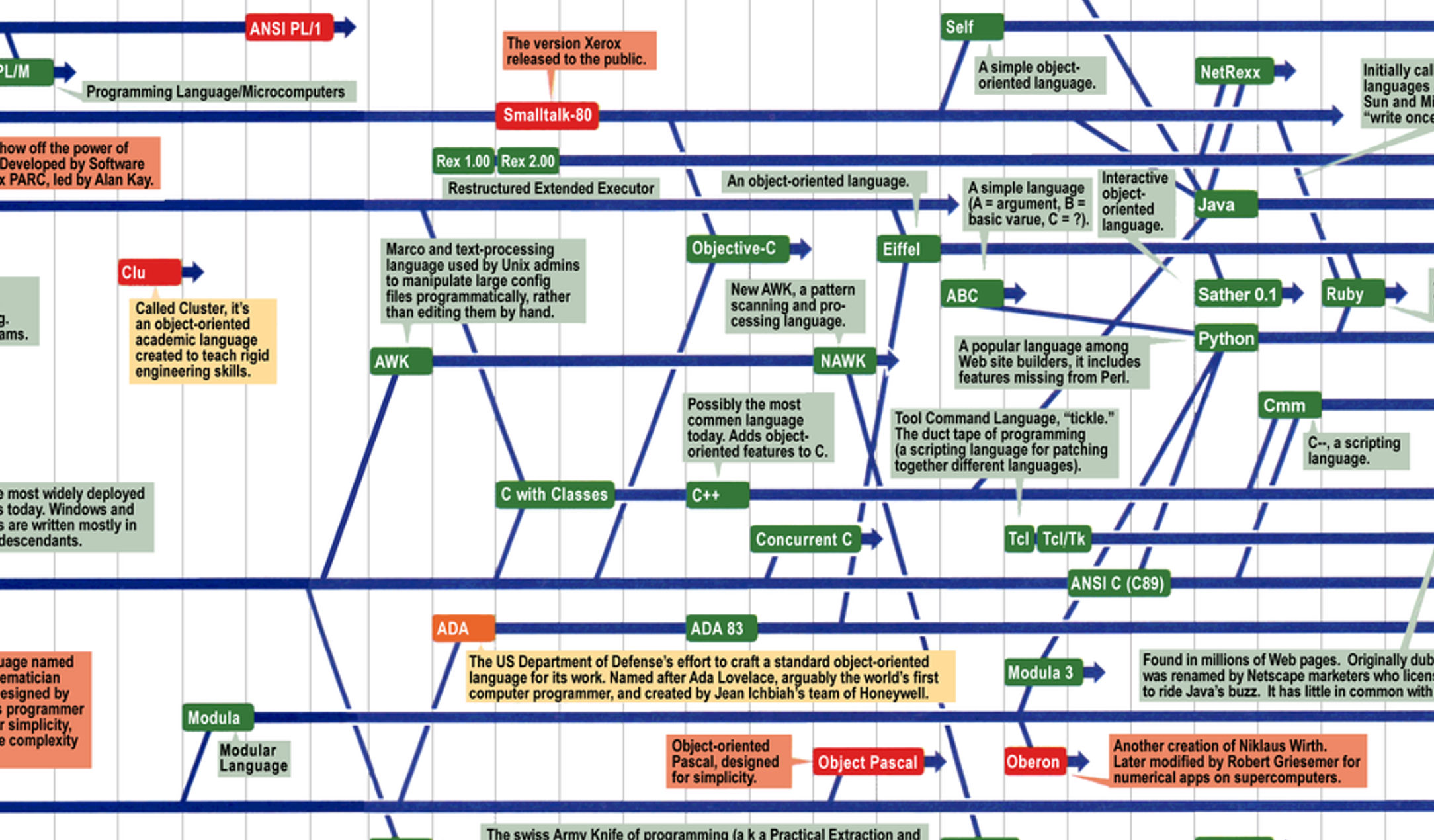

The blazing startup-time and lack of required installations in the C64 environment is, however, also a hint to its greatest weakness: lack of evolution in form of updates. Content of ROM-chip is read-only by definition, so Commodore Basic-hobbyists in 1988 were still using the same OS, same editing tools and same Basic-language as Commodore hobbyists in 1982. The fact modern PC-environment requires installation of several tools means that these tools can be updated to new better versions later. And with internet it's easy and quick to do such updates. The fierce competition of different languages, libraries and tools for hearts and minds of developers has been leading to rapid evolution of the capabilities of these technologies.

And how those capabilities have evolved! Consider following "feature comparisons"

Code editing experience

Even the most primitive text editors and word processors from 1990's onward have been based on following minimal basic principles:

- What you see on the screen is one continuous part of the program source code: Screen acts as a window to the source code.

- When you move cursor down from the last line of the visible source code or up from the first line, screen will scroll to reveal more source code in that direction.

- When you type characters on keyboard, the new characters are inserted to the program text at the cursor position.

However, Commodore 64 Basic-environment in 1980's did not work according these basic principles. Instead it worked more akin to a command-shell like the BASH-shell of Unix-systems or CMD-prompt of Windows-systems:

- On the screen you can write commands and press enter to execute the command.

- You can use

LIST-command to print to screen part of the program source code. But this just a copy of the code, just like printing content of a text-file to console withCAT(in Unix) orTYPE(in Windows) copies the content of a file to screen. Editing the content of the screen does not change the content of the Basic-program in memory. - Screen does not act as view or window to your code: even if you have printed some code to screen with

LIST, you cannot scroll upward or downward to reveal more code. If you want to see some other code not currently visible, you must give anotherLIST-command. - A command that starts with a number will create (or replace) a line from the program code with that line-number.

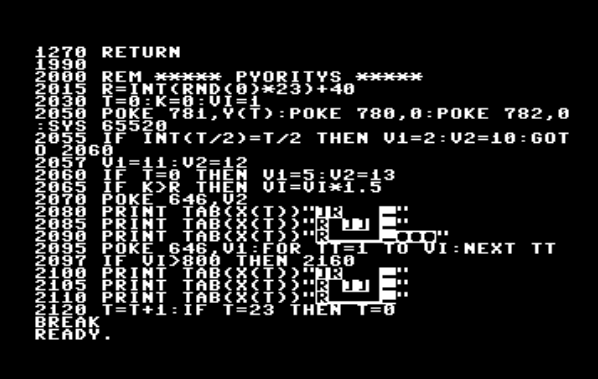

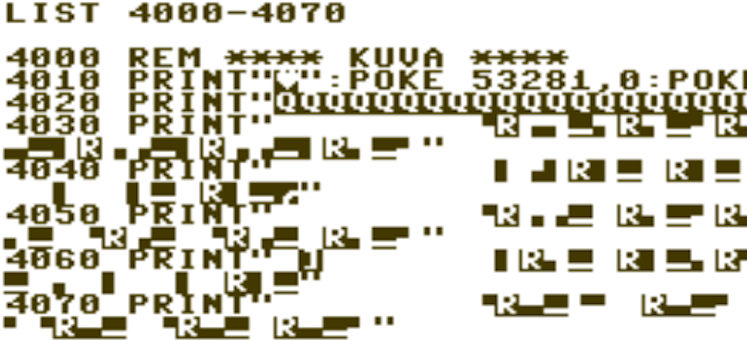

You can see the code... But you cannot scroll:

With these features it is not possible to directly "Edit" the source-code of the program. Closest we can get is to "editing" experience is by (1) LIST a line, (2) move cursor to the listed line, (3) overwrite some content of the listed line on screen and (4) press enter to execute the listed line as command which will overwrite the old version of the line in the Basic memory buffer.

What's a "line number" anyway?

Today when we talk of line-numbers of some source-code file, we mean the actual index of the line in the file: "Line 135" is the 135th line in the file. From the ruletti-64 source-code listing we can see that line numbers in C64 Basic meant an integer chosen by programmer and written in the beginning of the line. Having to work with such explicit line-numbers was quite a nuisance, but it was necessary evil for two reasons. First relates to the peculiar way of editing source code discussed above: since entering new or modified lines was not done in some ordered text buffer containing all lines but by execution of a command, the commands had to identify somehow the line in question and explicit line-number provided a way for that. Basic-programs were stored in memory as linked lists in order of increasing line number allowing replacement, insert or addition of line based on the given line-number.

Second, line-numbers provided a way to specify target-location for GOTO and GOSUB-commands. While more modern languages use string-identifiers for such things, integer line-number are more efficient, taking only fixed 16-bits of memory and being quick to compare.

Perhaps the biggest challenge with explicit line-numbers - and something that had to be often learned the hard way - was the possibility to write oneself "to the corner". The way to add a new between two existing lines was to add a line with line-number that was somewhere between the line-numbers of the existing lines. So if for example two consequent lines had number 205 and 209, you could add a line between them by using any line number between 205 and 209, say 207.

But what if you needed to add a line between lines with line numbers 205 and 206? You would be out of luck - can't do that, sorry, game over:

Because of this limitation a C64 Basic programmer with even little experience would not start writing programs with line numbers 1,2,3, etc: although that works initially fine, with such numbering its impossible to add any new lines between any existing ones. A common practice that I also used in Ruletti 64 source code was to number lines 10, 20, 30, ... and then the occasional in-between lines ending with 5 like 25... and hoping that one never ever needs to add more than 9 lines between two initial lines.

Bigger logical chunks of program - the subroutines - I started at big round lines 1000, 2000, 3000,... so that there is space to extend them when the program development progresses. This assumes maximum of 100 lines (with spacing 10) for each subroutine, which at least in this case was quite sufficient.

Editor Goodies

A modern program consists of multiple files and good editor allows keeping many files open at the same time and seamless navigation between the files to desired location. In contrast C64 Basic program is always just one file, one continuous list of lines. If one has a big program, then it's just a long single list. Although the limit of 38 kilo-Bytes available for Basic-program will be reached quite soon. Ruletti-64 game has 167 lines and size of 4.5 kB. With same average line size the memory limit would be reached with approximately 1500 lines - quite small piece of software by today's standards.

A simple operation that both programmers and writers use hundreds of times per day is Select + Cut + Paste to move text around. Nothing like that is available in C64: not even possibility to select text let alone copy or cut it. To copy lines to a different place in a program you must LIST them, then one by one edit a new line-number for the line and press enter. And before that better check that no other lines exist with the given numbers yet or else they will be overwritten. Moving larger groups of lines also becomes almost impossible since there is likely not enough free line-numbers available at the destination location (as explained in the previous chapter on line-numbers).

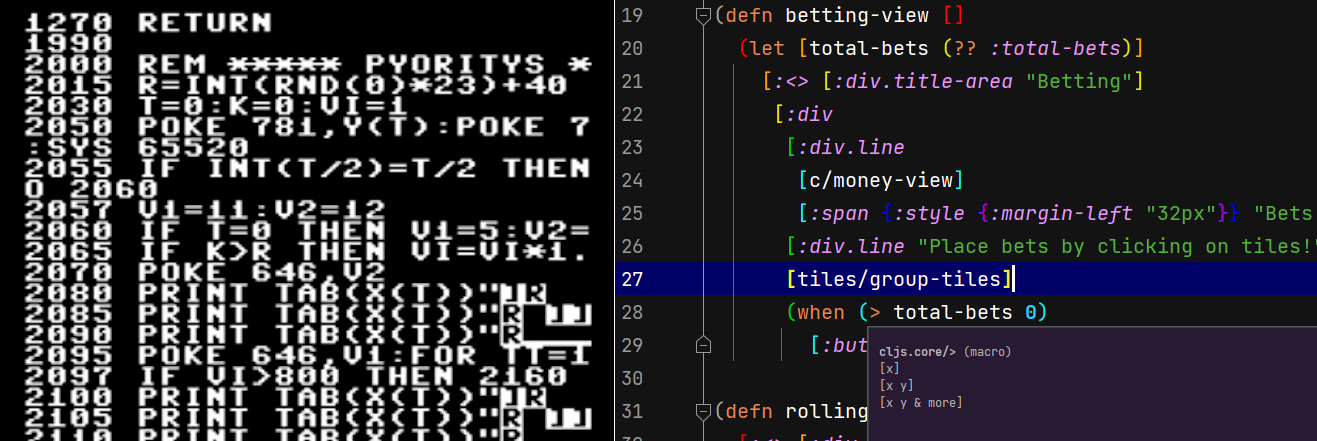

Users of modern editors like IntelliJ also enjoy many more advanced editing features that developers in 1980's could not even dream about:

- Multi-level UNDO for discarding edits gone wrong

- Syntax-highlighting that shows different parts of the code with different colors according to their grammatical role

- Error-highlighting that shows not only invalid syntax but also invalid function / variable references, unused variables, etc.

- Instant navigation from symbol reference to symbol definition and from definition listing all references.

- Instant context-sensitive documentation on selected function

- Code-completion or "intellisense" where editor suggests intelligently ways to auto-complete symbols, function-names, references, keywords and other common patterns

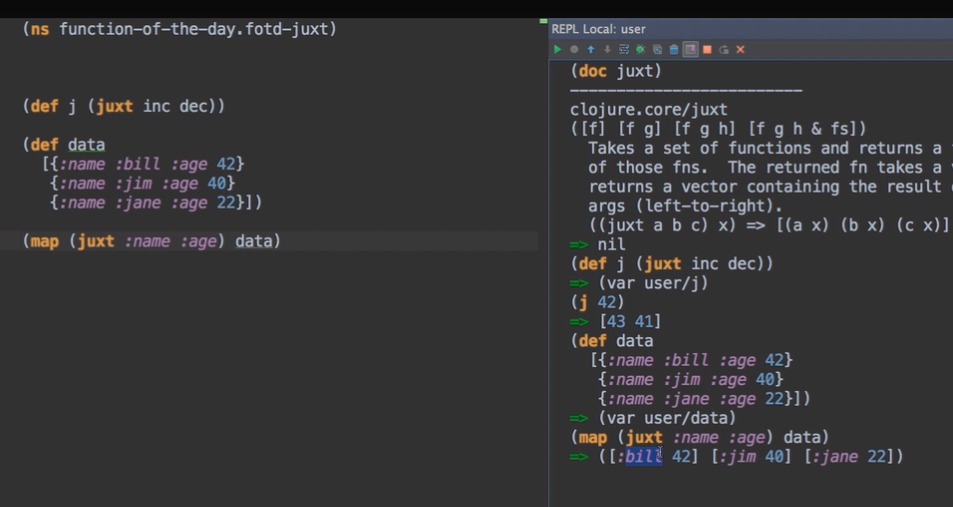

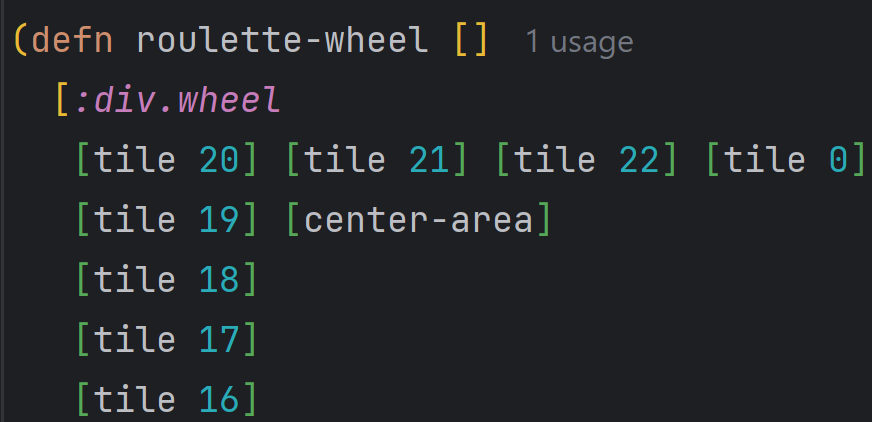

Plain code view of C64 Basic versus syntax-highlighting of Clojure in IntelliJ IDEA:

The IntelliJ IDEA editor with Cursive-plugin even supports special Structural Edition or "Paredit" for working with LISP-structures of Clojure. These allow easy and robust creation and editing of nested parenthesis-expressions as alternative to the more brittle copy/cut/paste.

Version Control and Backup

GIT revolutionized version control in 2005 and now over 80% of projects use this powerful version control system, including Ruletti-reframe in GitHub. But as much as GIT with its distributed design and lightweight branching is improvement over earlier popular systems like Subversion, those earlier systems were still much better than absolutely no version control at all like I had with developing C64 Ruletti.

While version control really shines in multi-person project, it is surprisingly useful even in a one-man hobby project. It makes it possible to easily back-up every step of the project to cloud and the freedom to experiment on drastic changes (delete and rewrite big chunks of code) without any risk of permanently losing anything. Making clean commit-packets of changes related to a new feature simplify later inspection and bring focus by identification and optional undoing of the changes related to the feature currently under development.

At the time of writing Ruletti 64 I did already have floppy-disk-drive which was huge upgrade to my earlier setup with C-cassette tape-drive. Still, that allowed at most the saving of some set of earlier versions of the code. And without any tools to compare or inspect these versions or have them opened at the same time or copy code between them, this was not very useful except for simple backup purposes. Though such backups were still valuable considering how easily the 5"25 floppy-disks used by C64 were getting corrupted.

Incremental Development, Hot Reload & REPL

Software development productivity is highly affected by the duration it takes to see results of code changes in running software. This change cycle delay can include time taken for (1) compiling the software, (2) starting up the software and (3) operating the software after startup to set up necessary location and state in the software to get the changed part of the code executed. In the 1960's and 1970's before Personal Computers many computer science students had to settle for change cycle delays as long as 24 hours: software source code was submitted on punched cards in the evening to computer science data center where the programs were compiled and executed during the night. Only on the morning the result of the execution was available to fetch and in the worst case result was that source code has some syntax error and the program execution could not even start.

Having your own computer like Commodore 64 at your home already gave an immense advantage over this. And since the C64 Basic-programs are interpreted, there is no compilation delay and program startup is almost instantaneous. However, the delay from operating the software to get to the location of changed functionality still remained. For example after making some improvement to the Ruletti 64 winnings calculation and display code, I had to re-start the game, place some bets and wait for the spinning to complete in order to see the result. If the result was not quite what I wanted, I had to stop the program, list the relevant lines again and start over. In parts of code that required several small incremental modifications this cycle delay could significantly hinder productivity. The problem here is not just the actual time wasted again and again for the steps to use the program but the loss of focus and development flow that this incurs.

Modern build tools like Shadow-cljs ClojureScript compiler practically eliminates this delay with a powerful hot reload feature. While the full compilation of the ClojureScript sources to JavaScript still takes 10-30 seconds, this only needs to be done once in the beginning of a development session. In hot reload the compiler tool watches in the background for any changes in source files while the program is running. When detected, the compiler compiles the changed files and any dependencies in the background and then reloads the changed files in the run-environment (browser in this case). Changes in the running program are in effect immediately (typically in less than 1 second).

Dropping of compilation time from the full 10-30 seconds to the hot reload incremental 1 second is nice, but the best aspect of this feature is that the reload is done without touching the program state. For example when I want to modify Ruletti-reframe winnings calculation and display, I need to play the game to the winnings screen only once after which I can do any number of incremental changes to the relevant code see each time result immediately in the UI. It's super delightful and effective and once experienced working in this way, one really does not want to go back to the need to re-start app after changes.

In the case of Clojure(Script) the hot reload can be enhanced further by REPL (Read Evaluate Print Loop) feature where custom commands and expressions can be evaluated from the keyboard interactively within the live running process of the game:

While hot reload can be used to quickly experiment with code, REPL adds quick experiments with program state and events. Even the humble Commodore 64 has primitive REPL as the main user interface to the system - individual Basic-statements can be written and executed interactively - but this is not withing running program context and requires the program execution to be stopped.

Deployment experience

Part of developers work and pain is to get the ready software to the hands of users. In this case even more than in the examples above, the developer experience has evolved from difficult and slow process to a simple delightful act.

The slow process in 1988 involved sending the game to the MikroBitti magazine on a diskette in post. After a two month delay the magazine printed the source code listing in their 1988/5 number. After which come the hardest part for the readers: typing the code to their computers from the listing accurately enough to run without errors. The slow process of deploying software to users meant that listings were published one time in one form and never updated. Only in some rare extreme cases where a listing contained a fatal bug, next magazine might contain a small correction.

All this has of course changed completely because of Internet and it's current extensive services. Internets TCP/IP protocol was standardized only in 1982 and in 1988 Internet was still only used by small circle of university researchers and not widely known about until around 1995. Slow and expensive modems did exist but were still relatively rare, and mainly for PC-hardware. Before widespread use of internet the modems were used around 1990-1995 of Bulleting Board Systems (BBS) that users could call in and swap messages and later pieces of software. MikroBitti magazine also set up their own BBS in 1994 for distributing software and that finally killed the remaining source-code listings in the magazine.

Now publishing the source code is just matter of one click and one second for pushing new commit to the free and unlimited GitHub repo. Deploying new version of the playable game is also just a two-line script that takes about one minute to compile the code and upload compiled files to AWS S3 bucket:

lein release

aws s3 cp resources/public s3://roulette-reframe/ --recursive

This makes the updated game version immediately available in URL http://roulette-reframe.s3-website.eu-north-1.amazonaws.com/ enabling true iterative development and feedback all the way to users.

Productivity boost

I worked on the original Ruletti-64 most of my free time for more than a month in 1987 before sending it for publication in 1988. This can be compared to the approximately six hours it took for me to finish the new Ruletti-reframe - even though the it has significantly improved UX and added features compared to the original.

While much of this ~10x productivity boost is explained by improvements in code- and architecture-technologies (which I will compare in another post), the effect of superior development tools discussed above should not be underestimated. Improvements since 1987 from humble copy-paste to context-sensitive help, code navigation, hot reload and version control could well contribute a 2x...5x factor of the total productivity gain. The architectural productivity advantages of good modern functional programming language are most pronounced in larger projects (> 10 000 lines of code) so in a small project like this game (< 1 000 lines of code) the effect of development environment and tools is even more pronounced.